The

Circus Menagerie

Before zoos began to develop in

North America, there was the circus menagerie. Traveling, tented circuses became popular in

America in the early years of the nineteenth century, and their story was

chronicled in William Cameron Coup’s 1901 book, Sawdust & Spangles: Stories & Secrets of the Circus. Coup was

born in 1837 and ran away to join the circus as a teenager. He was an eye

witness to its early history, which he wrote about in his book.

The supply of rare and exotic

creatures for these traveling menageries fueled a robust, international trade

in animals. According to Coup, there were at least two features of the animal

business before the turn of the twentieth century which were seldom

exaggerated. These features were the huge cost of stocking a menagerie and the

danger inherent in the capture and handling of the wild animals. Coup found it

thrilling to consider “the lives that have been lost, the sufferings and

hardships endured, the perils encountered, and the vast sums of money expended

in the capture and transportation of wild animals for the menageries, museums

and zoological gardens”.

After he became the head of a

circus, Coup had extensive dealings with the Reiche Brothers animal importers.

Charles Reiche ran the New York office while his brother, Henry, operated a

large supply farm in Germany that handled animals from around the world. Their

most extensive field operations were in Africa where they had numerous

stations, with sheiks or chiefs in their employ, and standing rewards offered

to natives for choice specimens of rare birds or beasts.

Jumbo

One of the most famous circus menagerie

animals of all time was killed at 9:30 in the evening on September 15th,

1885 when Jumbo the elephant was struck by a freight train while crossing the

tracks in St. Thomas, Ontario, Canada. Jumbo’s story began twenty-four years

earlier in Northern Africa when he was captured, sold to an animal dealer, and transported

across the Mediterranean. He spent time at the zoo in Paris and, in 1865, he was

shipped to England where he became a popular fixture at the London Zoo. He

eventually reached a height of about twelve feet at the shoulder and a weight

of about seven tons.

legendary and

Barnum wished to acquire the largest elephant in the world. He purchased Jumbo

from the zoo for ten thousand dollars. In March of 1882, after

considerable difficulty, Jumbo was packed into an enormous crate and left

England for America. He arrived in New York on April 9th with much

fanfare, and the next day he was displayed at Madison Square Garden. Jumbo

spent the next three years crisscrossing the Continent, transported in his own

train car. He drew huge crowds for Barnum, even though he performed no tricks

like the other elephants – merely his presence was enough.

From

Circus to Zoo

By the turn of the twentieth

century, circus menageries were the primary animal exhibitors in America. Few

American zoos had large animals, like elephants, since most zoos were little

more than deer parks. Circuses had far better collections and, of course,

reached larger and geographically broader audiences. In fact, the first

elephants, lions, rhinos, and hippos at many early American zoos came

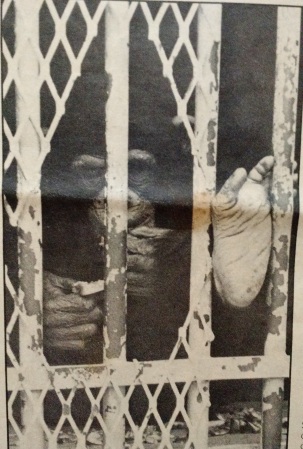

from circuses, and the zoo enclosures these animals entered were eerily like

the ones I encountered at the beginning of my career at the old Toronto Zoo,

nearly seventy years later.

Next #FridayBlog - the Toronto Zoo, Frank Buck, and "Bring Em Back Alive"

Next #FridayBlog - the Toronto Zoo, Frank Buck, and "Bring Em Back Alive"